PBT-NAS: mix architectures during training

Based on our paper “Shrink-Perturb Improves Architecture Mixing during Population Based Training for Neural Architecture Search” (ECAI 2023)

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) algorithms promise to automate neural network architecture design. And yet, despite the constant flow of papers claiming improved results, SOTA architectures are still designed manually. That’s a reality check if I ever saw one — but not the topic of today’s post (I’ll also skip for now the question if NAS is needed at all, or if you just need to literally “stack more layers”).

I believe that the dominating efficient NAS approach, weight sharing (see here for description), contributes to the missing impact of NAS on SOTA architectures: weight sharing cannot scale to the enormous sizes of current models. I also think that searching on scaled-down problems (less data, fewer filters, fewer layers) — another popular efficient approach — is problematic because architectures that are optimal only in a large-scale setting cannot be found by definition.

PBT-NAS is our attempt at an alternative approach to NAS efficiency, one that could potentially scale to SOTA results (although it has its own limitations, as discussed below).

This post is intended as a short and informal version of our paper, look there for more details.

From PBT to PBT-NAS

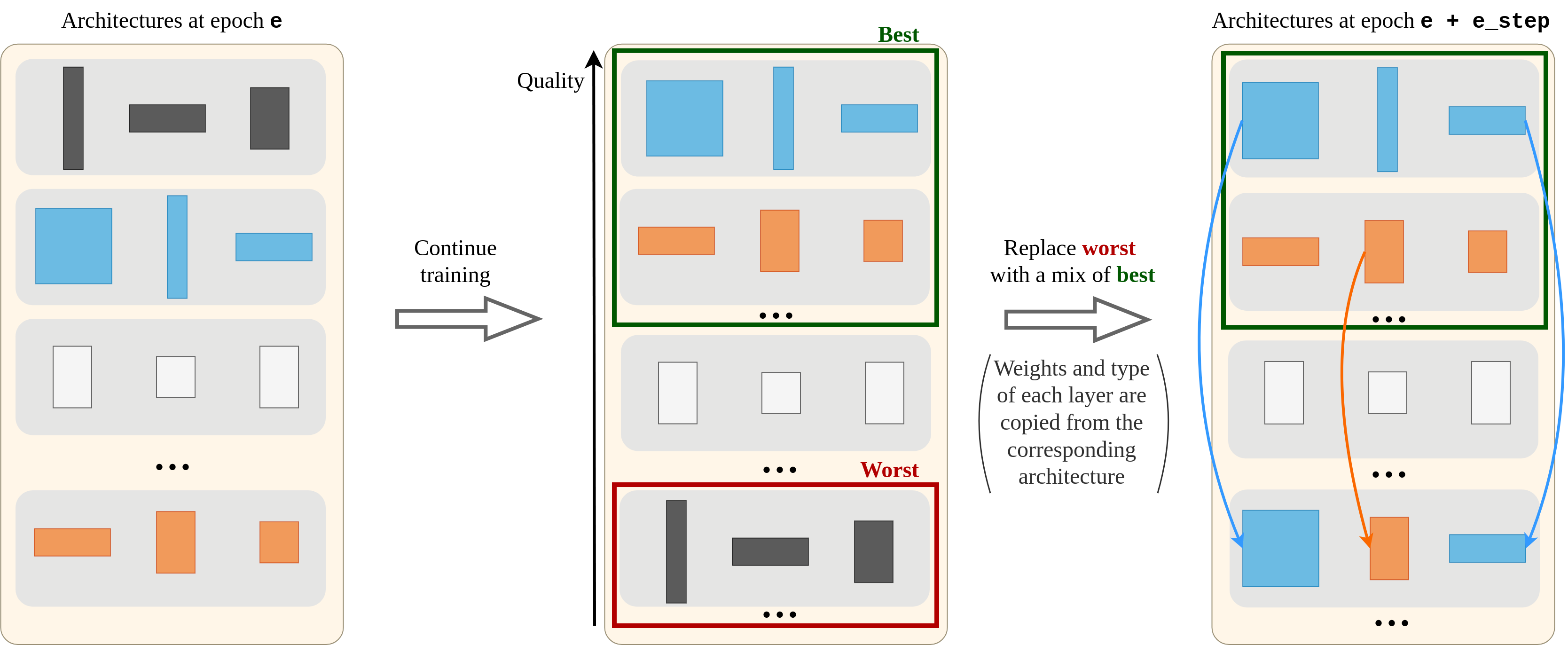

“PBT” in PBT-NAS is Population Based Training, an evolutionary algorithm for online hyperparameter optimization. N networks are trained in parallel with different hyperparameters, and periodically poor-performing networks are replaced with copies of well-performing ones, with the hyperparameters randomly perturbed. PBT is attractive because it is parallel, compute-efficient, and can be applied to large models directly, with the final model being usable immediately after search.

Hyperparameter exploration via random perturbations works for hyperparameter search, since hyperparameters can typically be replaced independently of the weights: if you changed the learning rate, you can still continue training the same weights.

But when architecture is searched, the weights are affected by the changes: what if you change layer type from linear to convolutional? The weights cannot be reused anymore.

Where then can we get the weights for the changed part of the architecture?

Well, you can always sample them randomly, but that might be quite a disruption for the network as a whole.

What if we do not randomly perturb the architecture but create it as a mix of two architectures from the population? Then the weights can be copied from the parent architectures!

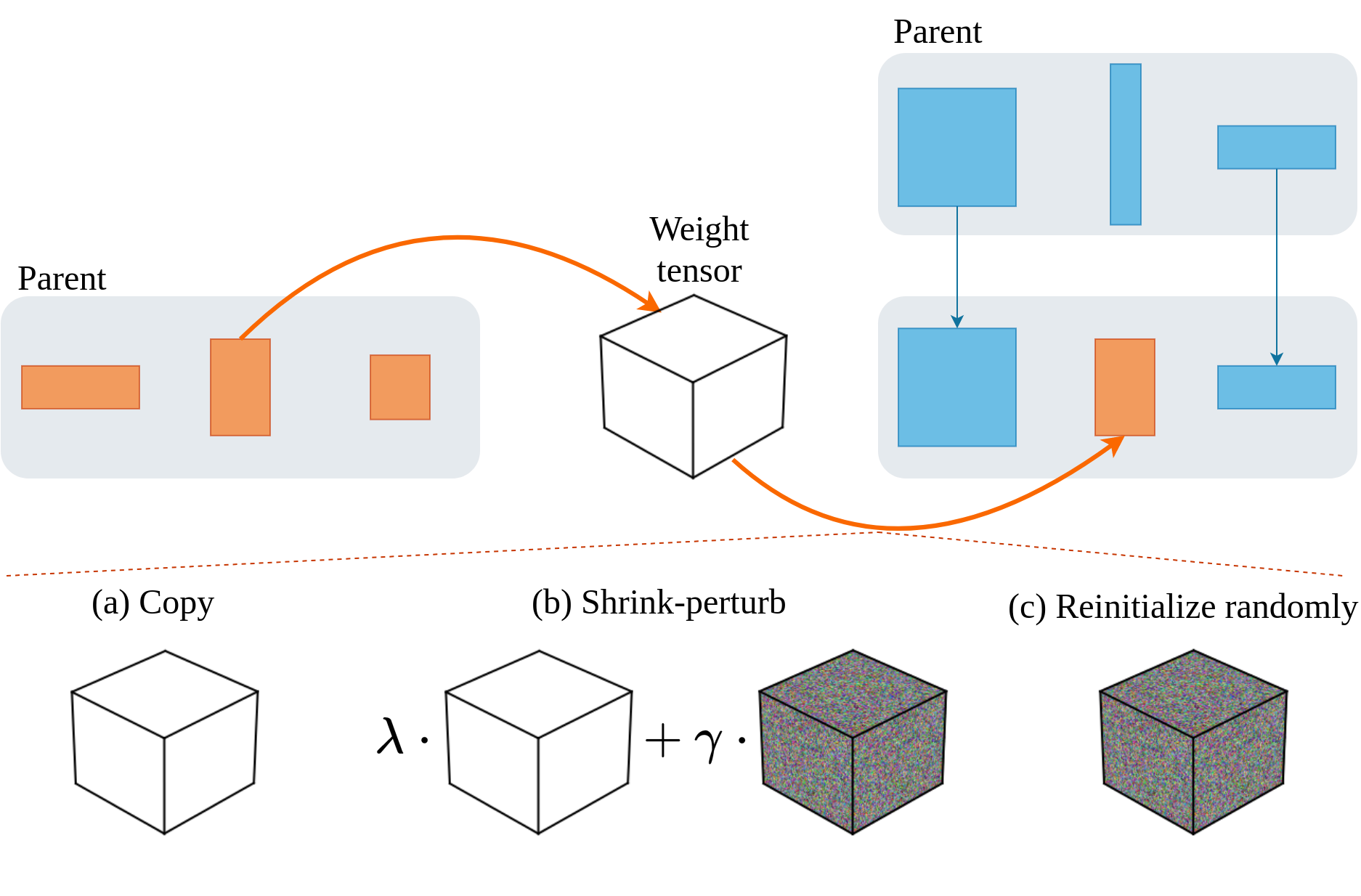

This is where shrink-perturb comes in. It was introduced in online learning to solve a specific problem: once new data arrives, continuing training is worse than retraining from scratch using all the data. Shrink-perturb modifies weights by shrinking (multiplying by a constant λ) and perturbing them (adding noise multiplied by a constant γ).

In essence, shrink-perturbing the weights is the middle ground between using them as-is and randomly reinitializing them. When mixing architectures for NAS, it both preserves useful information in the weights and injects randomness to potentially escape poor local optima.

Two networks can be mixed to create a new architecture by randomly copying layer from one of the parents in each position. The weights copied from the worse of the two parents can be shrink-perturbed to help their adaptation.

The ideas of exploring architectures via mixing and adapting weights with shrink-perturb are the key ideas of PBT-NAS. Exploring architecture online in this way allows PBT-NAS to be efficient, while avoiding restrictions brought by weight sharing.

Experiment setup

I have some strong opinions about the 0.1% improvements on CIFAR-10 classificaion commonly seen in NAS papers, as well as about NAS benchmarks where very good architectures (though technically not optimal) can be trivially found even by random search.

Therefore, I invested a lot of effort into creating actually challenging search spaces where differences between algorithms can be large, and working with challenging tasks: Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) training and Reinforcement Learning (RL).

For GANs, I wanted to simply use the search space from AdversarialNAS because the paper reported poor performance for random search, however in my experiments random search performed rather well, indicating that the search space may not be that hard. So I created a harder version of the search space, which also included options that could not be searched via the continuous relaxation approach of AdversarialNAS, such as whether a block should downsample, or how many projections from random noise to have.

For RL, I started with DrQ-v2, a SOTA algorithm for visual continuous control, and created search space based on the architectures used in all the components: encoder, actor, critic. I found several papers discussing ways to improve RL performance by scaling architectures via specific techniques (e.g. spectral normalization, transformer-like residual linear layer), and added those techniques as options to the search space.

Results

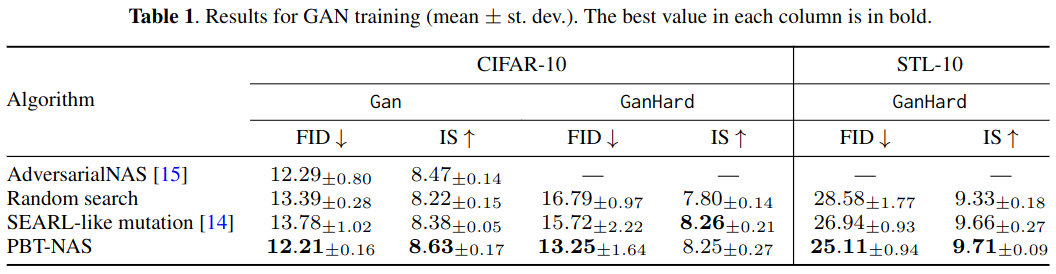

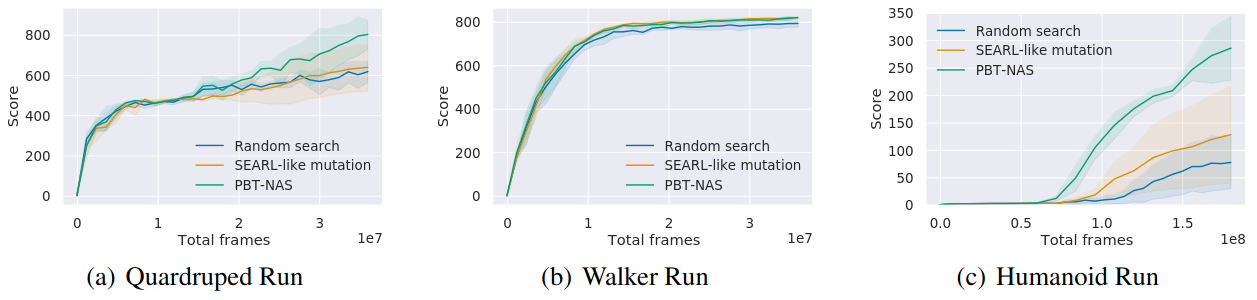

PBT-NAS outperformed random search and PBT with mutations in both GAN & RL settings. As the table below shows, the gap between algorithms is larger in the harder search space.

In the RL results, it can also be seen how on an easier task (Walker Run) there’s almost no difference between algorithms, while differences become visible with harder tasks (Quadruped Run, Humanoid Run). So having challenging search space is not enough, the task should be challenging too!

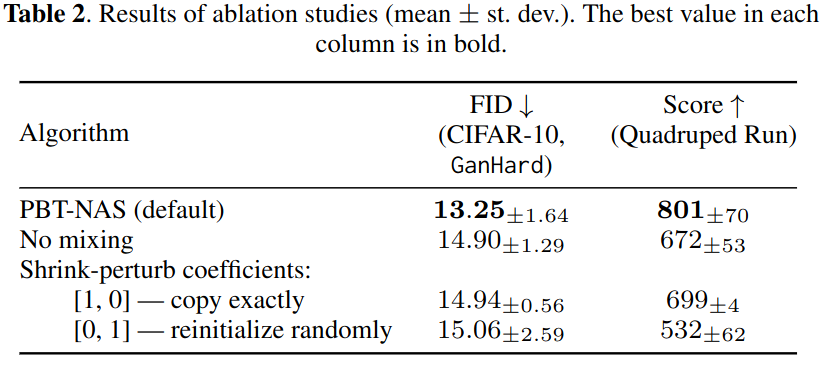

Personally, I find ablations to be more interesting than the “who has a better number” results, since ablations can show which parts of an algorithm actually do something.

We tested if mixing does anything by disabling it (“No mixing” in the table below): new architectures were created by mixing the model with itself, so no new architecture is created, but good architectures from the initial population still propagate. Performance drops, showing that creating new architectures is actually helpful.

We also compare shrink-perturb with copying weights as-is and with reinitializing them randomly. Both of those options perform worse, so shrink-perturb is a “golden middle” (I was also happy that I didn’t have to tune its parameters).

Limitations & Conclusion

PBT-NAS removes some limitations of weight sharing but still has some of its own. Firstly, the layer options at a specific position have to be interoperable: after swapping one layer for another, the next layer should still be able to take the layer’s output as its input. Secondly, PBT-NAS is greedy: the networks are selected based on their intermediate performance, so if it correlates poorly with the final performance, suboptimal-in-the-long-term architectures could be selected.

Still, PBT-NAS performs well in challenging settings, and is a non-standard approach to efficient NAS. I think we could all benefit from having more of those.

The paper contains more experiments & fewer hot takes, the code is public.